In November and December of last year (2023), team of Eda’s researchers conducted a study on improvements and changes in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in BiH. This involves a new research approach used within the new approach to the theory of change – the Vector theory of change, developed by Dave Snowden for introducing changes in complex systems. Traditional theories of change typically involve envisioning an endpoint (vision) and then working backwards to identify steps leading to that goal, with reasons and assumptions provided for each step. In complex systems and environments, traditional theories of change show their limitations, as they rely on the assumption of planned predictability of steps (interventions) based on a clear cause-and-effect relationship, which is absent or cannot be established in advance in complex situations. The Vector theory of change reverses this approach and shifts the focus from high-level long-term goals to a cyclical approach containing four steps: (1) start from your current situation/state; (2) set the direction of change and find stepping stones (like stones for crossing a river); (3) design interventions, and (4) constantly monitor feedback. More about the vector theory of change can be read here.

We aimed to recognize the behavior/action patterns of small and medium-sized enterprises in introducing improvements/changes/innovations (step 1 of the vector theory of change) and to assess whether these improvements enable them to move to the next step towards resilience as the main direction of development and condition for survival in an environment characterized by increasingly sudden and stronger shocks and disruptions. Therefore, in addition to better understanding the current state, we also wanted to gain initial insights and assumptions for the second step, both starting from the perspective of the enterprises themselves.

The research utilized SenseMaker, a tool that enables the collection and analysis of short narratives/stories based on the personal experiences of respondents, who themselves give meaning to their narratives instead of having someone else do it. A total of 60 stories were collected, with the largest number from enterprises in the agriculture and food production sector, followed by metal processing, textile industry, wood processing, and other activities. The structure of respondents by enterprise size corresponds to the structure of enterprises in the country, with the largest number being micro and small enterprises, followed by medium-sized enterprises, and a smaller number of large enterprises.

This type of research differs from standard research as it is thematically more challenging and practically more interesting in its execution. It is different primarily because the participants in the research have the main role in choosing their experiences and insights to include in the research, as well as in interpreting their meanings. Moreover, it is interesting for both participants and researchers, encourages reflection, and enhances understanding of the real situations we find ourselves in and wish to improve.

Through the research, we aimed to deepen the understanding of the specific challenges faced by enterprises and to identify opportunities for improvements aimed at ensuring the development of enterprises. Among the wealth of useful information and new hypotheses this research brings, we found two aspects particularly interesting: (1) Can coherent patterns of introducing improvements and changes in SMEs be identified, i.e., can a dominant pattern be established in most stories, and what does this pattern tell us? and (2) Can the next level of improvement that SMEs are considering be assessed, i.e., the type of next improvement that is, at least partially, enabled by the current improvements? These aspects and the answers to these two questions are the focus of this blog.

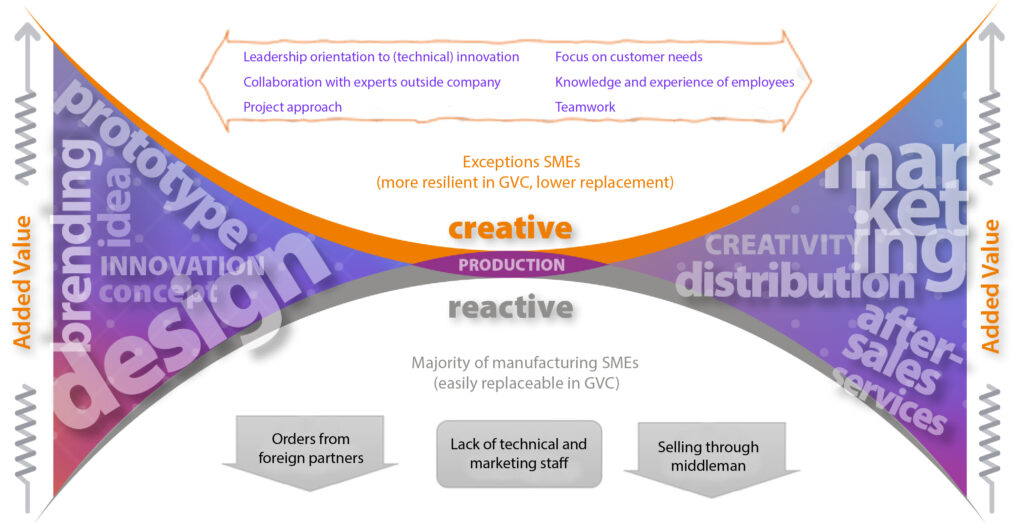

Results show that currently, in introducing innovations, the “internal” perspective (focus on efficiency, cost reduction, desire to improve own performance) dominates over the “external” view (market opportunities, attention to customers). This largely closed perspective is likely doubly conditioned: (1) by the position in international value chains, where export-oriented SMEs are required to continuously “tighten” their production; and (2) by the weak domestic institutional environment that does not allow enterprises to move on to more ambitious innovations in terms of products and business models.

The so-called smile curve well illustrates the position of most of our export-oriented SMEs, which are mainly focused on production for a known customer, i.e., working according to a pre-defined order specifying what and how, within what time frame, and at what cost should be produced.

Such a position brings a relatively low level of added value for the enterprise, with the risk of other functions (research and development, marketing, etc.) either not developing or withering away, ultimately leading to an unacceptably low level of resilience to the increasingly frequent, sudden, and stronger disruptions occurring in international value chains. This pattern and its background show a high level of coherence with risk management and the use of resources in introducing improvements. The largest number of enterprises faced an overload of their own resources or capacities (technical and financial), most used their own funds to finance these investments, some combined them with grant funds, and very few used loan funds. In addition to external limitations (low availability of higher quality professional staff, lack of newer financial arrangements such as venture capital investment), serious internal limitations in terms of availability and quality of professional staff, as well as quality financial management within enterprises, can also be assumed.

When delving into the content of the stories, it can be seen that they predominantly involve smaller, internal improvements that are controllable, executable in a shorter time frame, and not too complicated but can be carried out according to a pre-defined plan with the help of experts. Larger companies undertook relatively larger improvements, which were carried out with much greater difficulty than expected.

After participants in the research “told” their story about recent or ongoing improvement and positioned it in appropriate triangles and dyads, they were given the opportunity to hint at the next priority for improvement, which was not possible before completing the previously described investment.

Most enterprises cited the development of new products and the potential to expand production to new markets as the next priority. Additionally, enterprises are planning significant investments in promotion and marketing, with the aim of conquering new markets. A significantly smaller number of responses indicated process improvement and the acquisition of new equipment as the next priority. When looking again at the “smile curve,” such prioritization shows a shift in focus for the next cycle of innovation, from the production phase, i.e., cost reduction and efficiency improvement, to the left side (new product development) and the right side (marketing and new markets).

It is probably too early for hasty conclusions about whether production SMEs are ready for a gradual transition to a smarter and more resilient business model, which to a greater extent includes orientation towards the development of their own new products and strengthening the marketing function, i.e., introducing a business philosophy where marketing and creating greater added value play a more significant role. Such orientation has so far been observed in a smaller number of enterprises, which differed from others in their openness to innovation and support from key decision-makers, greater focus on the needs of more demanding and selective customers, a solid level of knowledge and experience of employed experts, and significant cooperation with experts outside the enterprise, teamwork, and project approach.

If it is too early for a conclusion, it is not too early for a hypothesis about the increased level of readiness of production export-oriented SMEs in BiH for innovations leading to a more resilient, smarter, and profitable business. There seem to be enough reasons in the mentioned research to establish such a hypothesis. Additional research and practical experiments with enterprises showing readiness and potential for such changes are needed to confirm it. Our team sees new opportunities and tasks in this regard.

On the other hand, the findings of various studies and research lead to the serious establishment of a hypothesis that within BiH, at no administrative level, is there anything close to a system of support for SME innovations, or an innovation ecosystem, that would significantly enable and facilitate such a newly observed orientation of enterprises. It seems to me that this aspect requires fewer additional studies and research and more concrete conceptual and practical steps towards establishing and/or completing such an ecosystem.